Introduction to Hash Algorithms

See also What is Perceptual Hashing, NSA builds secret backdoors in the new encryption standards

Earlier, we looked at hashtables and how we can use them to to store and retrieve values very efficiently. The core to making data structures like the hashtable actually work is the hash function. Now, we did talk about hash functions as part of our hashtable exploration, but we only scratched the surface of what they are. They are a very useful concept to fully understand on their own because we will encounter them all the time in cases like the following:

- Data storage and retrieval

- Password verification

- File integrity checking

- Digital signatures

- Data deduplication

- ...and more!

It’s definitely a good idea for you and I to back up a bit and learn all about what hash functions are and how to write our own from scratch just to get a better understanding of the complexities involved.

Onwards!

What is a hash function?

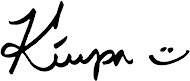

Taking a very high-level birds-eye view, a hash function is a mathematical function that takes an input (aka "key" or "message") and turns it into an output (aka "digest"):

Let’s dive into what exactly the input and output are in greater detail.

The Input

The typical input to a hash function can be any type of digital data, including:

- Text – Strings, passwords, documents, or any textual information.

- Files – Images, videos, executables, or any file type.

- Binary Data – Network packets, database records, cryptographic keys.

- Numbers – Integers, floating-point values, or structured numerical data.

To state that more formally, a hash function takes arbitrary-length input and maps it to a fixed-length output. The input size can be as tiny as a single byte or as ginormous as an entire file or dataset.

The Output

The typical output of a hash function is a fixed-length string or number, which represents the input data uniquely (or as uniquely as possible). The length of the output depends on the specific hash function used. The hash function we will create from scratch in a few moments will be just a few characters in size. A more involved hash function we will look at later is going to be 32 characters in length!

Criteria for a Great Hash Function

As we will find out shortly, it’s easy for any function to become a hash function. For a function to be a great hashing function, well...that takes some effort. There are a few guidelines that good hash functions should follow:

- Deterministic - The same input must always produce the same output hash value. No randomness or variation is allowed.

- Uniform Distribution - Hash values should be spread evenly across the possible range to minimize clustering and collisions.

- Fast Computation - The hash function should be computationally efficient and quick to calculate, typically in O(1) time.

- Avalanche Effect - Small changes in the input should result in significant changes in the output hash value.

- Fixed Output Size - The hash function should generate fixed-length output values regardless of input size.

- Low Collision Rate - Different inputs should rarely produce the same output hash value. When collisions do occur, they should be handled gracefully.

- Non-Reversible - For cryptographic hashes, it should be computationally infeasible to reconstruct the original input from the hash value.

- No Correlation - There should be no discernible patterns between similar inputs and their corresponding hash values.

These seem like a lot of guidelines, but they are important for a hash function to follow. If any of these guidelines aren’t followed, many situations where a poorly written hash function is used in could fall apart easily. Given the mission-critical nature that hash functions are typically used in, that is a big problem.

Creating our own Hash Function

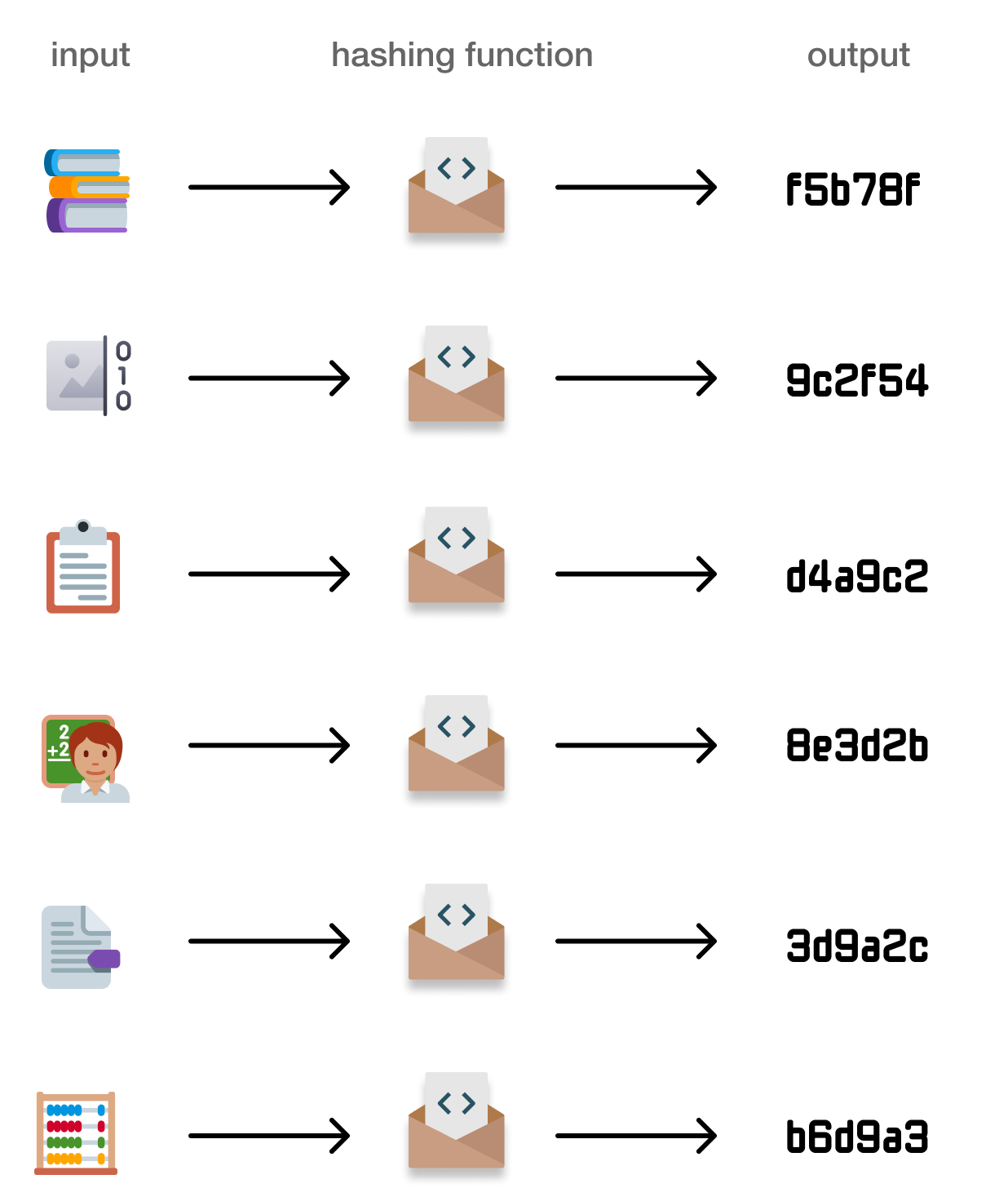

Putting our theoretical hat aside for a moment, one of the best ways to learn about hash functions is to just create one! We will build upon the simple one we saw earlier, where our hash function will primarily work on text, and it will work by:

- Adding up the character codes of each character in our input

- Clamping the range (aka table / bucket / slot size) to a prime number like 37

Let’s say we want to encode the word hello using this particular hash function. Here is this visualized:

If we turn all of this into JavaScript, we would have something like the following:

function simpleHash(str, tableSize = 37) {

let hash = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < str.length; i++) {

let charCode = str.charCodeAt(i);

hash += charCode;

}

return hash % tableSize;

}

// Example usage

console.log(simpleHash("hello")); // 14

This code shows how any text based input will result in a hash value, using the logic we described above.

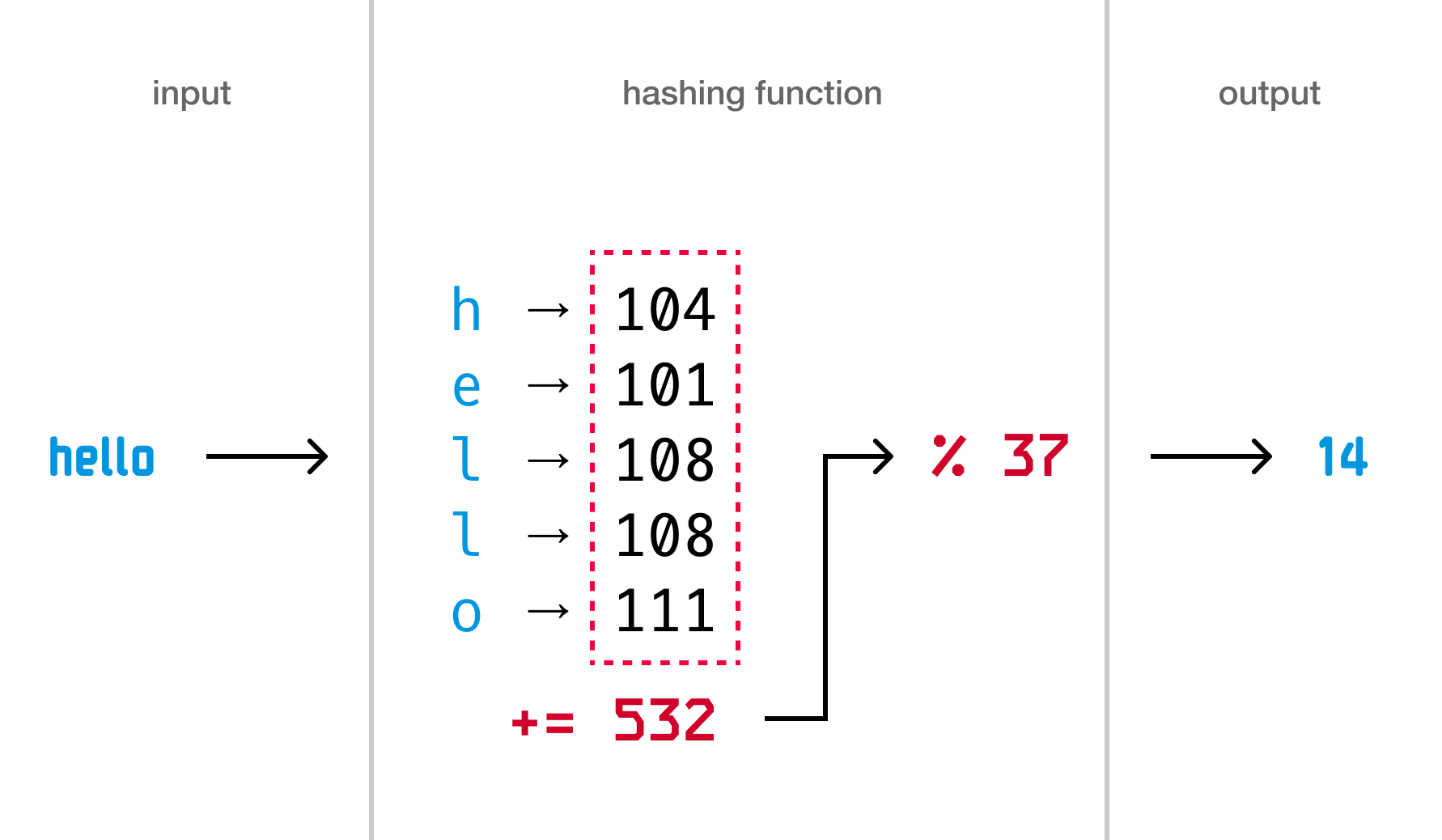

One thing we call out in our code and explanation is this thing called table size. What is table size? The table size in hashing refers to the number of "buckets" or "slots" available for our hashing function to put things into:

To explain differently, it’s the range of possible output values that our hash function can produce, and this value is often a prime number to help reduce the chances of collisions.

Now, our current hash function is not a great one. It fails most of the criteria for a great hash function that we called out earlier. For example, take a look at the output for the distinctly different values: hello and olleh:

console.log(simpleHash("hello")); // 14

console.log(simpleHash("olleh")); // 14

For these two different inputs, the output is exactly the same. They both return a value of 14. That’s not good, for ideally we would want our hash function to provide a unique value when the inputs look very different.

The reason for this collision is due to how we defined our hashing logic. Because our approach only sums up the character codes of our string, many combinations of same length words with the same letters (even if they are arbitrarily arranged) will always return the same output value. Because of how different character codes combine, there will also be cases of different length words returning the same output as well. This isn’t good. We need to strengthen our hash function to do better.

One way to strengthen our hash function is by adding a position weighting to each letter:

function simpleWeightedHash(str, tableSize = 37) {

let hash = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < str.length; i++) {

let charCode = str.charCodeAt(i);

hash += charCode * (i + 1);

}

return hash % tableSize;

}

// Example usage

console.log(simpleWeightedHash("hello")); // 26

console.log(simpleWeightedHash("olleh")); // 21

This revised approach takes into account both the character code as well as changes in a letter’s position. With this modification in place, our hash function will now ensure that hello and olleh return different outputs.

Now, using the guidelines we called out earlier, even with this revision, our hash function has a lot of room to improve. In its current state, it fails almost all of them. We are not going to fix our hash function further, for the point to emphasize here is that creating a good hash function is not trivial. It takes a fair amount of work to have one that can be used in real-world situations. For that reason…

Always Use an Existing Hash Function

If you (or a friend!) need a hash function, use one that is already built into your favorite language/framework or use any of the popular implementations for MD5, SHA/SHA1, and SHA2.

For an example of a hash function that is well-designed and meets all of the guidelines we called out earlier, this MD5 variant is a good study:

// Simplified version of a popular md5 implementation

// Original copyright (c) Paul Johnston & Greg Holt.

function md5(inputString) {

var hc = "0123456789abcdef";

function rh(n) {

var j,

s = "";

for (j = 0; j <= 3; j++)

s +=

hc.charAt((n >> (j * 8 + 4)) & 0x0f) + hc.charAt((n >> (j * 8)) & 0x0f);

return s;

}

function ad(x, y) {

var l = (x & 0xffff) + (y & 0xffff);

var m = (x >> 16) + (y >> 16) + (l >> 16);

return (m << 16) | (l & 0xffff);

}

function rl(n, c) {

return (n << c) | (n >>> (32 - c));

}

function cm(q, a, b, x, s, t) {

return ad(rl(ad(ad(a, q), ad(x, t)), s), b);

}

function ff(a, b, c, d, x, s, t) {

return cm((b & c) | (~b & d), a, b, x, s, t);

}

function gg(a, b, c, d, x, s, t) {

return cm((b & d) | (c & ~d), a, b, x, s, t);

}

function hh(a, b, c, d, x, s, t) {

return cm(b ^ c ^ d, a, b, x, s, t);

}

function ii(a, b, c, d, x, s, t) {

return cm(c ^ (b | ~d), a, b, x, s, t);

}

function sb(x) {

var i;

var nblk = ((x.length + 8) >> 6) + 1;

var blks = new Array(nblk * 16);

for (i = 0; i < nblk * 16; i++) blks[i] = 0;

for (i = 0; i < x.length; i++)

blks[i >> 2] |= x.charCodeAt(i) << ((i % 4) * 8);

blks[i >> 2] |= 0x80 << ((i % 4) * 8);

blks[nblk * 16 - 2] = x.length * 8;

return blks;

}

var i,

x = sb("" + inputString),

a = 1732584193,

b = -271733879,

c = -1732584194,

d = 271733878,

olda,

oldb,

oldc,

oldd;

for (i = 0; i < x.length; i += 16) {

olda = a;

oldb = b;

oldc = c;

oldd = d;

a = ff(a, b, c, d, x[i + 0], 7, -680876936);

d = ff(d, a, b, c, x[i + 1], 12, -389564586);

c = ff(c, d, a, b, x[i + 2], 17, 606105819);

b = ff(b, c, d, a, x[i + 3], 22, -1044525330);

a = ff(a, b, c, d, x[i + 4], 7, -176418897);

d = ff(d, a, b, c, x[i + 5], 12, 1200080426);

c = ff(c, d, a, b, x[i + 6], 17, -1473231341);

b = ff(b, c, d, a, x[i + 7], 22, -45705983);

a = ff(a, b, c, d, x[i + 8], 7, 1770035416);

d = ff(d, a, b, c, x[i + 9], 12, -1958414417);

c = ff(c, d, a, b, x[i + 10], 17, -42063);

b = ff(b, c, d, a, x[i + 11], 22, -1990404162);

a = ff(a, b, c, d, x[i + 12], 7, 1804603682);

d = ff(d, a, b, c, x[i + 13], 12, -40341101);

c = ff(c, d, a, b, x[i + 14], 17, -1502002290);

b = ff(b, c, d, a, x[i + 15], 22, 1236535329);

a = gg(a, b, c, d, x[i + 1], 5, -165796510);

d = gg(d, a, b, c, x[i + 6], 9, -1069501632);

c = gg(c, d, a, b, x[i + 11], 14, 643717713);

b = gg(b, c, d, a, x[i + 0], 20, -373897302);

a = gg(a, b, c, d, x[i + 5], 5, -701558691);

d = gg(d, a, b, c, x[i + 10], 9, 38016083);

c = gg(c, d, a, b, x[i + 15], 14, -660478335);

b = gg(b, c, d, a, x[i + 4], 20, -405537848);

a = gg(a, b, c, d, x[i + 9], 5, 568446438);

d = gg(d, a, b, c, x[i + 14], 9, -1019803690);

c = gg(c, d, a, b, x[i + 3], 14, -187363961);

b = gg(b, c, d, a, x[i + 8], 20, 1163531501);

a = gg(a, b, c, d, x[i + 13], 5, -1444681467);

d = gg(d, a, b, c, x[i + 2], 9, -51403784);

c = gg(c, d, a, b, x[i + 7], 14, 1735328473);

b = gg(b, c, d, a, x[i + 12], 20, -1926607734);

a = hh(a, b, c, d, x[i + 5], 4, -378558);

d = hh(d, a, b, c, x[i + 8], 11, -2022574463);

c = hh(c, d, a, b, x[i + 11], 16, 1839030562);

b = hh(b, c, d, a, x[i + 14], 23, -35309556);

a = hh(a, b, c, d, x[i + 1], 4, -1530992060);

d = hh(d, a, b, c, x[i + 4], 11, 1272893353);

c = hh(c, d, a, b, x[i + 7], 16, -155497632);

b = hh(b, c, d, a, x[i + 10], 23, -1094730640);

a = hh(a, b, c, d, x[i + 13], 4, 681279174);

d = hh(d, a, b, c, x[i + 0], 11, -358537222);

c = hh(c, d, a, b, x[i + 3], 16, -722521979);

b = hh(b, c, d, a, x[i + 6], 23, 76029189);

a = hh(a, b, c, d, x[i + 9], 4, -640364487);

d = hh(d, a, b, c, x[i + 12], 11, -421815835);

c = hh(c, d, a, b, x[i + 15], 16, 530742520);

b = hh(b, c, d, a, x[i + 2], 23, -995338651);

a = ii(a, b, c, d, x[i + 0], 6, -198630844);

d = ii(d, a, b, c, x[i + 7], 10, 1126891415);

c = ii(c, d, a, b, x[i + 14], 15, -1416354905);

b = ii(b, c, d, a, x[i + 5], 21, -57434055);

a = ii(a, b, c, d, x[i + 12], 6, 1700485571);

d = ii(d, a, b, c, x[i + 3], 10, -1894986606);

c = ii(c, d, a, b, x[i + 10], 15, -1051523);

b = ii(b, c, d, a, x[i + 1], 21, -2054922799);

a = ii(a, b, c, d, x[i + 8], 6, 1873313359);

d = ii(d, a, b, c, x[i + 15], 10, -30611744);

c = ii(c, d, a, b, x[i + 6], 15, -1560198380);

b = ii(b, c, d, a, x[i + 13], 21, 1309151649);

a = ii(a, b, c, d, x[i + 4], 6, -145523070);

d = ii(d, a, b, c, x[i + 11], 10, -1120210379);

c = ii(c, d, a, b, x[i + 2], 15, 718787259);

b = ii(b, c, d, a, x[i + 9], 21, -343485551);

a = ad(a, olda);

b = ad(b, oldb);

c = ad(c, oldc);

d = ad(d, oldd);

}

return rh(a) + rh(b) + rh(c) + rh(d);

}

Here is what this hash function returns for hello:

console.log(md5("hello")); // 5d41402abc4b2a76b9719d911017c592

It returns a fairly incomprehensible 32 character-length string made up of letters and numbers. If we gave it a slightly different value like Hello (where the H is capitalized) the output now is:

console.log(md5("Hello")); // 8b1a9953c4611296a827abf8c47804d7

The returned value is a very VERY different 32 character-length string than what we saw for hello even though we changed just a single letter. That’s a good sign!

Just for kicks, let’s walk through our guidelines and see whether this md5 hash function meets the bar for being a good hash function. The results are:

- Deterministic? Yes. The same input always returns the same hash value.

- Uniform Distribution? Hard to prove with just a few examples by ourselves, but MD5 is popular enough to have a lot of public confirmation of this.

- Fast Computation? Yes. The code looks complex to us as humans, but to our computers, it is lightning-fast with no loops or other things that could slow things down, especially for large inputs.

- Avalanche Effect? Yes. See the above hello vs. Hello example where a small change in the input results in a huge change in the output.

- Fixed Output Size? Yes. The output of an MD5 hash is always 128 bits (16 bytes) long. When represented as a hexadecimal string, it is 32 characters long.

- Low Collision Rate? Yes. There are 128 bits, which means there are (2128) possible hash values. That’s a pretty large surface area where, especially for smaller datasets, you’ll rarely ever see a collision.

- Non-Reversible? Yes. MD5 reduces any input (small or large) into a fixed 128-bit hash, discarding excess information. Once hashed, you cannot easily reconstruct the original input

- No Correlation? Yes again. A small change in the input will product a different enough output without any rhyme or reason provides as to why

If you are up for it, definitely study popular hashing functions like MD5 and understand deeply how they work. Pay particular attention to how they try to avoid clustering where common input values will lead to a collision where the same output is generated. That is one of the hardest things to get right. For a much more thorough hashing function implementation, one that can't reasonably be shown in a single page here, check out the implementations of the SHA functions. Those are so good that they are primarily used in complex cryptography!

Conclusion

Hashtables and related data structures are extremely fast because they rely on hashing functions. Beyond just performance, hashing functions are literally everywhere. They protect our passwords by storing only their hashed versions, verify that file downloads haven't been tampered with, help generate digital signatures, and more. Because of the critical role they place in so many computing activities, hopefully this deep dive into hashing functions gives you a better understanding of what they are and how they work.

Just a final word before we wrap up. What you've seen here is freshly baked content without added preservatives, artificial intelligence, ads, and algorithm-driven doodads. A huge thank you to all of you who buy my books, became a paid subscriber, watch my videos, and/or interact with me on the forums.

Your support keeps this site going! 😇