Ad libitum dehydration is associated with poorer performance on a sustained attention task but not other measures of cognitive performance among middle‐to‐older aged community‐dwelling adults: A short‐term longitudinal study

Asher Y. Rosinger

52–66 minutes

1 INTRODUCTION

Hydration status is critical for optimal physiological health with far-ranging effects on multiple aspects of human biology ranging from cellular health, kidney function, and mood (Popkin et al., 2010). Recent work has demonstrated that poor hydration was associated with biological acceleration of age, higher risk of chronic disease, and earlier mortality (Dmitrieva et al., 2023). As an essential nutrient, people should consume an amount of water that is appropriate for them based on their sex, age, body composition, physical activity levels, and environmental conditions, including heat and humidity taking into account both outdoor and indoor thermal conditions (Food and Nutrition Board & Institute of Medicine, 2004; Rosinger, 2023). When water intake shortfalls occur, dehydration takes place, and this is posited to negatively affect cognitive performance. A growing body of work has examined the relationship between experimentally-induced moderate dehydration and cognitive ability and performance (Adan, 2012; Bethancourt et al., 2020; Białecka-Dębek & Pietruszka, 2018; D'Anci et al., 2006; Fadda et al., 2012; Ganio et al., 2011; Goodman et al., 2019; Grandjean & Grandjean, 2007; Trinies et al., 2016; Wittbrodt & Millard-Stafford, 2018).

The question of how hydration status affects cognitive performance matters for human biology because this relates to a fundamental problem associated with human water needs. People's bodies generally adapt to the level of water they are used to consuming and their biomarkers of hydration status match the amount they consume daily (Johnson et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2016; Rosinger, 2020). If people chronically consume low amounts of water, this is reflected in higher serum osmolality (Sosm), which is buffered against acute changes in water intake (Armstrong, 2007). This relationship is particularly important in middle-aged and older adults given that they are more vulnerable to dehydration than younger adults due to a gradual decoupling of thirst from hydration status (Kenney & Chiu, 2001; Rolls & Phillips, 1990; Suhr et al., 2004); this occurs at a time when there are also declines in cognitive function.

Despite a popular narrative that dehydration impairs cognitive performance, results are mixed in the literature. A 2018 meta-analysis examining the effects of dehydration from 1%–6% body mass loss found a significant effect, particularly after 2% dehydration for tasks involving attention, executive functioning, and motor coordination (Wittbrodt & Millard-Stafford, 2018). However, a follow-up meta-analysis in 2019 (Goodman et al., 2019)—that limited the scope to 10 experimental studies using crossover designs—found that cognitive performance and its subdomains were not significantly impaired by dehydration, though the overall effect size was negative. By limiting to crossover designs, this second meta-analysis aimed to avoid the bias found in the prior meta-analysis by matching cognitive performance after exercise with and without dehydration.

Further complicating our understanding of this relationship is the complexity in assessing the exposure in real-life settings. Most research examining this relationship relies on stimulating dehydration through fasting, passive heat, exercise, or a combination of these factors (Ganio et al., 2011), which makes it hard to tease apart the effect of hydration status from the conditions which also have potential effects on cognitive performance (Deshayes et al., 2022). In daily life, people generally do not undergo severe water loss, unless they are endurance runners or work in physically demanding settings in extreme heat. Yet, cross-sectional, observational designs cannot untangle directionality of results (Bethancourt et al., 2020; Grandjean & Grandjean, 2007; Masento et al., 2014; Suhr et al., 2004). Ad libitum conditions, where hydration status is not manipulated can provide evidence of how hydration status influences cognitive performance in daily life.

One recent longitudinal study of ad libitum conditions among older Spanish adults examined the effect of both physiological hydration status measured through serum osmolarity and water intake amounts on cognitive performance 2 years later (Nishi et al., 2023). That study found that being dehydrated as defined by high serum osmolarity at baseline, but not water intake levels, predicted declines in cognitive performance. Yet, the study was conducted among a sample with metabolic syndrome, thus declines in cognitive performance may have been influenced by cardiometabolic disease (Nishi et al., 2023). A key gap in the literature is a lack of short-term longitudinal iterations between ad libitum hydration status and cognitive performance. That is, we are missing studies, in which participants have both hydration status and the cognitive performance tests assessed multiple times in real-life settings without induced dehydration but without sufficient time elapsing that other factors including aging or other comorbidities known to influence cognitive decline affect the relationship.

Therefore, we conducted a short-term longitudinal study among middle-to-older aged US adults measured three times over 3 months in which we assessed serum osmolality as a gold standard biomarker of hydration status and four cognitive performance tasks. Based on prior work, we hypothesized that being dehydrated would result in poorer cognitive performance, particularly for tasks with sustained attention (Bethancourt et al., 2020).

2 METHODS

Data come from an observational longitudinal study conducted at Pennsylvania State University in 2019–2020. The study's primary aim was designed to evaluate associations between biomarkers of stress (e.g., cortisol production following a social stressor) and novel measures of inflammation (i.e., stimulated cytokine production) that may predict age-related health problems (e.g., cardiovascular disease, cognitive decline), with secondary aims related to hydration. The study had a target sample size of 70 participants as power was computed to detect an effect with the primary aims, though not secondary outcomes. Participants were recruited from the surrounding areas to State College, Pennsylvania. The study collected information on participant demographics, including educational attainment, prescription medication usage, and age. Exclusion criteria included the use of NSAIDs or medication due to the potential effects it would have on inflammatory data (also collected and analyzed in other studies). All participants were instructed to avoid high-fat foods, caffeine, and exercise on the days of the visits. All participants were scheduled for 8:00 a.m. visits for the baseline, two-week, and three-month examinations where they completed surveys, neuropsychological tests to measure cognitive performance, anthropometrics, and had blood drawn for biomarker analysis (all blood draws occurred between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m.). All participants were weighed on a Brecknell MS140-300 scale with height measured on a wall-mounted stadiometer without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as kg/m2. More detail about the study has been published elsewhere (Davis et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2023; Guevara & Murdock, 2020; Murdock et al., 2022).

All study procedures were approved by The Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board (STUDY00008161) and were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent prior to beginning study procedures.

2.1 Outcomes: Cognitive performance

Inhibition, a higher order executive function task, was measured via performance on the color-word interference test from the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) (Delis et al., 2001). This task has been widely used in the literature and demonstrates excellent validity and reliability (Latzman & Markon, 2010). Two conditions were used to form an overall score, including the inhibition and inhibition/switching conditions. On the inhibition condition, participants were asked to name the color of the ink that a list of color-words are printed in, rather than reading the word, as quickly as possible. During the inhibition/switching condition, participants were asked to switch between stating the color of ink that the list of color-words are printed in and reading the word depending on whether the word is enclosed in a box. The time to complete each task and the total number of errors on the tasks were z-scored and combined to form an overall indicator of inhibition. This was then reverse scored such that higher scores were associated with better inhibition ability.

Working Memory was measured through the digit span task from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV) (Wechsler, 2008). This task, along with other variants of digit recall and manipulation, are frequently used as measures of updating/monitoring throughout the literature (e.g., [Richardson, 2007]). During the digit span task, a trained research team member provided lists of numbers of varying length to the participant. Digits associated with each numbered list were presented at one-second intervals. The length of the numbered list increased as one progressed through each of the three conditions. There were no time restrictions for participant responses. The first condition is characterized by participants being asked to simply repeat the list of numbers in the same order as the research team member presented them. In the second condition, the participant was asked to state the list of numbers in the reverse order of which they were read to them. For the last condition, participants were asked to order the numbers provided to them from lowest to highest. The total number of correct responses across the tasks and the largest number of digits recalled correctly from the first condition were z-scored and combined to form an indicator of updating/monitoring.

Cognitive flexibility was measured through the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), computerized version (Heaton & Par, 2000). The WCST is a widely used and validated measure of cognitive flexibility in clinical and experimental settings (Chan et al., 2008). During the test, four cards of different shapes, colors, and numbers are displayed to the participant who is asked to match the cards; however, they are not informed as to which qualities to match the cards on. After each move, the participant is told whether the move was “right” or “wrong” and the classification rule is changed every 10 cards such that the participant must adapt to the new rule. Indicators of perseverative responses, perseverative errors, and non-perseverative errors were z-scored and combined, then reverse-scored, to form an overall indicator of cognitive flexibility with higher scores indicating better performance.

Sustained attention or the ability to focus on a stimuli or signal for a period, was measured through the Conners' Continuous Performance Test, Second Edition (CPT-II) (Conners, 2000). During the test, black letters are presented on a white background one at a time on a computer screen. The participants were asked to press the spacebar as quickly as possible each time they saw a new letter, unless that letter was “X.” Each letter presented reflects a single trial, and this was repeated 360 times over a 14-min period. T-scores associated with the percentage of omissions (i.e., failing to press the spacebar when presented with a letter other than “X”) and commissions (i.e., pressing the spacebar when presented with an “X), as well as response speed consistency (i.e., the degree to which response speed changed over time), were z-scored and combined to form an overall indicator of sustained attention. These values were reverse scored such that higher scores are associated with better sustained attention.

2.2 Predictor: Serum osmolality (Sosm)

Hydration status was assessed using Sosm, which is the measure of dissolved particles in blood and is considered a gold standard measure of hydration status (Wutich et al., 2020). Blood samples were frozen and stored at −80°C. Samples were removed from the freezer and allowed to thaw at room temperature, then briefly vortexed. We measured Sosm in the Water, Health, and Nutrition Lab via freezing point depression osmometry using an Osmo1 (Advanced Instruments) single-sample 20 microliter micro-osmometer. After calibration of standard solutions (50, 290, and 800 milliosmoles per kilogram [mOsm/kg]), all blood samples were measured in duplicate with the average measure used in the analysis, using the correction associated with the 20 microliter sample measurement (Sollanek et al., 2019). Higher osmolality reflects a higher concentration of solutes in the bloodstream, indicating relatively less fluid volume with levels >300 mOsm/kg, signifying dehydration (Thomas et al., 2008).

2.3 Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed in Stata V15.1 (College Station, TX) with statistical significance set to p = .05. All cognitive outcome variables were z-standardized before being combined, thus 0 represents the median in the z-curve.

We first used fractional polynomial fit scatterplots to illustrate the dispersion of data and the bivariate association between Sosm and the four measures of cognitive performance with the data pooled across the three visits. While there was some visual evidence of nonlinearity, no significant quadratic relationships were found (p values ranged from .15 to .92 for the four outcomes; full results not shown). Thus, in primary regression models we analyzed Sosm as a dichotomous variable at the cutoff for dehydration because there is a biologically meaningful state of dehydration at 300 mOsm/kg, which is clinically recognized to affect physical and mental health outcomes (Lacey et al., 2019). Variation in a Sosm between 280 and 300 (considered a euhydrated state) generally would not be expected to have much effect on cognitive performance until reaching beyond 300. To verify this assertion, we first estimated models with Sosm as a continuous variable (per 5-mOsm/kg increase) on the measures of cognitive performance.

We used panel random effects linear regression models with robust standard errors and fixed time effects to examine the longitudinal relationship between dehydration and cognitive performance to be able to adjust for time invariant factors—that is, factors that do not change over the 3 months. Two models for each outcome were assessed. Model 1 analyzed the effect of dehydration on cognitive performance adjusting for time fixed effects so that individuals served as their own controls across time. Model 2 additionally adjusted for covariates that may influence both hydration status and performance on cognitive tasks (Bethancourt et al., 2020; Brooks et al., 2017; Rosinger et al., 2016), including sex (male/female), age (in years), BMI (kg/m2), and educational attainment (categorized as (1) receiving a high school degree or less [reference group], (2) some college education, associates, or vocational school, and (3) a college degree and above).

To test the robustness of the results, we reestimated the fully adjusted models with a balanced panel restricting the sample to participants with data at all three visits who had no missing data for each component.

3 RESULTS

Demographic characteristics as well as hydration status and cognitive performance tasks are presented stratified by the three visits in Table 1. For the first visit, 73 participants had information on all cognitive measures and Sosm and were on average 60.5 years old, 76.4% female, 95% white, and had an average BMI of 27.4. Differences in sample size across the three time points related to either problems with the blood draw or missing a follow-up appointment; however, there were no differences in demographic characteristics among those missing compared to the overall sample as age, sex, BMI, and educational attainment levels remained consistent across the three timepoints (Table 1). Overall, there were 78 unique participants with a maximum of 207 observations across the three time points.

TABLE 1. Demographic characteristics of the sample in each visit for those with serum osmolality measured.

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or % | Mean or % | Mean or % | |

| --- | --- | --- | |

| (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | |

| --- | --- | --- | |

| Sample size | 73 | 67 | 69 |

| Age (years) | 60.5 (6.1) | 60.9 (6.1) | 60.9 (6.3) |

| Sex (% female) | 76.4% | 78.8% | 76.5% |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4 (5.5) | 27.4 (5.7) | 27.8 (5.7) |

| Education: high school or less | 20.8% | 21.3% | 19.1% |

| Some college or associates | 44.4% | 43.9% | 48.5% |

| College degree or greater | 34.7% | 34.8% | 32.4% |

| Serum osmolality (mOsm/kg) | 298.4 (4.7) | 298.1 (4.9) | 299.0 (5.3) |

| Dehydrated (Sosm >300 mOsm/kg) | 35.6% | 29.9% | 39.1% |

| Inhibition (z-score) | −0.11 (2.3) | 0.05 (2.7) | 0.06 (2.4) |

| Working memory (z-score) | 0.01 (1.9) | −0.01 (1.9) | −0.1 (1.9) |

| Cognitive flexibility (z-score) | 0.11 (2.8) | 0.07 (2.8) | 0.04 (3.0) |

| Sustained attention (z-score) | −0.03 (1.7) | 0.08 (2.2) | 0.02 (2.1) |

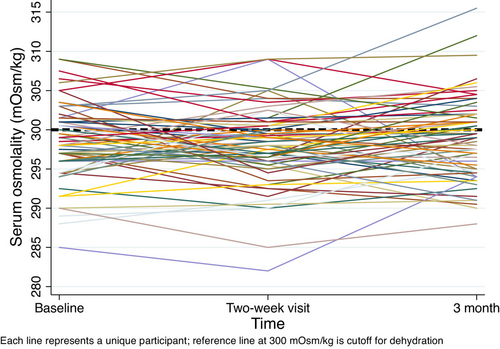

Across the three time points, there was more variation between participants than within participants (between-subjects variability SD = 4.26; within-subjects variability SD = 2.60) indicating relative stability within individuals over time (Figure 1). The overall mean Sosm was 298.5 (SD = 5.0). In the first visit, the average Sosm was 298.4 mOsm/kg with 35.6% of participants categorized as dehydrated (Sosm >300 mOsm/kg) (Table 1). For the second visit, the average Sosm was 298.1 mOsm/kg and 29.9% of participants were classified as dehydrated. For the third visit, the average Sosm was 299.0 mOsm/kg and 39.1% of participants were classified as dehydrated.

Longitudinal comparison of variation in serum osmolality among participants across visits. n = 78 (n = 207 observations).

3.1 Bivariate analyses

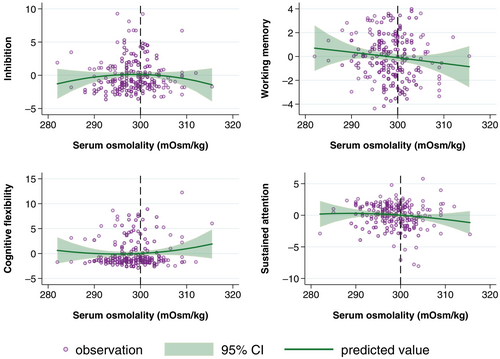

In bivariate analyses pooling all three visits, fractional polynomial fit plots demonstrate a slight inverse association between Sosm and three of the four measures of cognitive performance (Figure 2). First, Sosm had a mild concave relationship with inhibition scores, with lower scores at the extremes. Second, Sosm was inversely associated with working memory but had a wide dispersion of data. Third, Sosm had no association with cognitive flexibility, with a mild positive association at the highest Sosm, which may have been driven by two outliers. Finally, Sosm and sustained attention displayed an inverse association, particularly when Sosm was above 300 mOsm/kg.

Functional polynomial fit plot examining the association between serum osmolality and inhibition, working memory, cognitive flexibility, and sustained attention z-scores pooled for the three visits. Reference line >300 mOsm/kg is classified as dehydration.

3.2 Regression analyses

In both the unadjusted and adjusted panel random effects linear regression models with Sosm treated as a continuous variable, there were negative slopes between Sosm and inhibition, working memory, and sustained attention, which did not meet the statistical cutoff for significance (Table S1). However, both working memory and sustained attention had effect sizes that approached practical importance, where each 5-point increase in Sosm was associated with a decline in approximately a fifth of a standard deviation in the respective domains (working memory B = −0.21 z-score; SE = 0.11; p = .069; sustained attention B = −0.20 z-score; SE = 0.14; p = .16) (Table S1, models 4 and 8).

When Sosm was treated as a dichotomous variable, both unadjusted and adjusted panel random effects linear regressions demonstrate that there was only a significant association between dehydration and sustained attention (Table 2, models 1.1–1.8). The models testing the association between dehydration and inhibition and working memory had negative relationships in the expected direction, but were not statistically or practically significant. For working memory, the effect size was smaller than in the continuous models. Cognitive flexibility showed no association in the adjusted model with hydration. In contrast, adults who were dehydrated (Sosm >300 mOsm/kg) performed significantly worse (B = −0.65 z-score; SE = 0.28; p = .020) on the sustained attention task (equivalent to two-thirds a standard deviation) than those who were not dehydrated adjusting for covariates and time fixed effects (Table 2, model 1.8).

TABLE 2. Random effects panel linear regression examining the association between dehydration and measures of cognitive performance and attention.

| Model 1.1 | Model 1.2 | Model 1.3 | Model 1.4 | Model 1.5 | Model 1.6 | Model 1.7 | Model 1.8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition | Inhibition | Working memory | Working memory | Cognitive flexibility | Cognitive flexibility | Sustained attention | Sustained attention | |

| --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | |

| --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| Dehydrated | −0.07 (0.30) | −0.13 (0.29) | −0.12 (0.21) | −0.13 (0.21) | 0.08 (0.30) | 0.01 (0.29) | −0.68** (0.28) | −0.65** (0.28) |

| Age (per 1 year) | 0.09** (0.04) | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.00 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.02) | ||||

| Sex (ref: male) | −0.32 (0.64) | −0.54 (0.52) | −1.14 (0.84) | 0.08 (0.31) | ||||

| BMI (per kg/m2) | 0.10* (0.06) | −0.07* (0.04) | 0.09 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.02) | ||||

| Education: ≤high school | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Some college or associates | −0.67 (0.70) | 0.19 (0.48) | −0.39 (0.78) | 0.04 (0.32) | ||||

| ≥College degree | −0.82 (0.77) | 0.93* (0.56) | −1.22 (0.77) | 0.04 (0.35) | ||||

| Time 1 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Time 2 | 0.06 (0.18) | 0.02 (0.18) | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.10 (0.27) | 0.10 (0.27) | 0.07 (0.43) | 0.06 (0.44) |

| Time 3 | −0.07 (0.17) | −0.06 (0.17) | 0.11 (0.17) | 0.13 (0.17) | −0.03 (0.31) | −0.04 (0.32) | 0.09 (0.37) | 0.06 (0.38) |

| Observations | 207 | 205 | 206 | 204 | 201 | 199 | 199 | 197 |

| n | 78 | 77 | 78 | 77 | 77 | 76 | 78 | 77 |

- Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. Dehydrated: Sosm >300 mOsm/kg.

Robustness analyses demonstrated consistent results when the analysis was restricted to adults who were present in all three visits (Table 3). Again, dehydration was only associated with the sustained attention task (B = −0.60; SE = 0.30; p = .043) (Table 3, model 2.4). Performance on the four cognitive tasks was not significantly different across the three time points in any models (Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 3. Robustness analysis of balanced panel random effects linear regression examining the association between dehydration and measures of cognitive performance and attention.

| Variables | Model 2.1 | Model 2.2 | Model 2.3 | Model 2.4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition | Working memory | Cognitive flexibility | Sustained attention | |

| --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | Beta (SE) | |

| --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| Dehydrated | −0.11 (0.31) | −0.02 (0.23) | −0.34 (0.29) | −0.60** (0.30) |

| Age (per 1 year) | 0.12** (0.05) | 0.00 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.03) |

| Sex (ref: male) | −0.46 (0.76) | −0.62 (0.60) | −0.11 (0.74) | 0.17 (0.38) |

| BMI (per kg/m2) | 0.05 (0.06) | −0.07 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.01 (0.02) |

| Education: ≤high school | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Some college or associates | −0.08 (0.75) | −0.28 (0.55) | −0.03 (0.93) | −0.09 (0.27) |

| ≥College degree | −0.13 (0.83) | 0.62 (0.60) | −1.07 (0.74) | −0.14 (0.33) |

| Time 1 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Time 2 | −0.11 (0.19) | 0.08 (0.18) | −0.06 (0.26) | 0.17 (0.51) |

| Time 3 | −0.16 (0.19) | 0.18 (0.19) | −0.09 (0.31) | 0.37 (0.45) |

| Observations | 171 | 168 | 162 | 153 |

| n | 57 | 56 | 54 | 51 |

- Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. Dehydrated: Sosm >300 mOsm/kg.

4 DISCUSSION

This study aimed to assess if worse ad libitum hydration was associated with poorer cognitive performance longitudinally. In partial support of our hypothesis, we found that dehydration was associated with worse performance on a sustained attention task that lasted 14 min but was not associated with cognitive performance tasks related to inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. The sustained attention task requires high levels of attention throughout the task, whereas in the other cognitive tasks, participants get small breaks between items where they do not need to pay attention strongly.

As research into the human biology of water needs has expanded, it is critical to delineate how variation in water access and meeting one's water needs may become embodied in physiological and cognitive health (Rosinger, 2023). Our findings that in an ad libitum state middle-to-older aged adults who were dehydrated performed two-thirds a standard deviation worse on a sustained attention task than those who were not dehydrated represents a practically large effect size. These results are consistent with prior cross-sectional work (Bethancourt et al., 2020). Our short-term longitudinal study over 3 months confirms this finding and extends it to indicate that the effect persists and that it is likely biologically, rather than only statistically, meaningful (Valeggia & Fernández-Duque, 2022). Echoing the meta-analysis (Goodman et al., 2019) that examined crossover studies with experimentally induced dehydration following exercise versus maintaining a well-hydrated state, a 2022 crossover study with 10 physically active adults, who were habituated to hypohydration, found no effect on cognitive performance when measures of sustained attention were not included (Deshayes et al., 2022). In terms of comparing our findings of inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility, which measure subdomains of executive function with past work, a meta-analysis using active experimental dehydration found nonsignificant effects between dehydration overall and at the 2% limit and these subdomains, though all the relationships and effect sizes were negative and approximately −0.1–−0.2, in line with our results (Goodman et al., 2019).

Generally, there is a decoupling of thirst from hydration status whereby the thirst mechanism does not kick in until ~1% dehydration (Kenney & Chiu, 2001). This is hypothesized to have been important during human evolution as it allowed people to venture farther from their home base for hunting, gathering, and performing any other tasks without being tied to a water source (Rosinger, 2020). Importantly, prior work has demonstrated that older adults exhibit reduced thirst thresholds and sensitivity to changes tied to hydration status and consume less fluid compared with younger adults (Kenney & Chiu, 2001; Rolls & Phillips, 1990). Therefore, there is also a delicate balance. How long people go without drinking water, along with their awareness of needing to drink water, affects their hydration status, which can affect their productivity, physical performance (Murray, 2007), and mood (Armstrong et al., 2012; Ganio et al., 2011). What we find in the current study is that among middle-to-older aged adults ad libitum hydration status may also extend to cognitive performance tasks that require sustained attention. But overall, the fact that we do not see any relationship between ad libitum dehydration and performance on three other cognitive performance tasks means that humans can be flexible in meeting their water needs without severe repercussions on a daily basis. Adults may also be less sensitive to cognitive effects of acute body water deficits than children, who have been shown to have poorer performance on tests when they are dehydrated (Bar-David et al., 2005; D'Anci et al., 2006; Fadda et al., 2012). This likely occurs because of greater body water volume and lower surface area to mass ratio, which allows adults to better buffer the thermic effects of dehydration.

The implications of our results matter for water intake recommendations in advising how maintaining adequate hydration may affect cognitive performance (Association EFS, 2010; Food and Nutrition Board & Institute of Medicine, 2004). In daily life, most tasks require sustained attention in people's occupations. Yet the way many prior studies have tested cognitive performance includes measures that do not measure sustained attention (Goodman et al., 2019; Wittbrodt & Millard-Stafford, 2018), and may be less representative of daily life. While the sustained attention task we used is not necessarily representative of what people do at their jobs, it at least mimics a task that takes more than a couple of minutes to complete without small breaks in between trials (Conners, 2000). Ultimately, the effects of hydration status on cognitive performance may only emerge on longer tasks that do not include small breaks in required attention. As dehydration negatively affects mood and increases irritability (Armstrong et al., 2012; Benton & Young, 2015; Ganio et al., 2011; Masento et al., 2014), it is possible that being well-hydrated increases one's patience and persistence in tasks. Maintaining proper hydration throughout the day then may have small effects that emerge over the course of a day.

With global climate change driving hotter ambient outdoor and indoor temperatures that increase water needs (Kenney & Chiu, 2001), the influence on cognitive performance is important to track especially with an aging global population to best advise this vulnerable group. Therefore, it will be important to determine whether hydration relates to declines in cognitive performance over time. Importantly, a prior study found that worse physiological hydration predicted declines in two-year change in global cognitive functioning; however, this was among participants who met criteria for metabolic syndrome (Nishi et al., 2023). It will be important to evaluate this association over time among both healthy and nonhealthy populations to best determine the association between hydration and risk of cognitive decline.

4.1 Strengths, limitations, and future directions

This study has several strengths. First, the study design eliminated many confounders present in other observational and cross-sectional studies as our longitudinal analysis used individuals as their own controls over three time points. Second, visits all took place at the same time in the mornings to avoid the effects of exercise, caffeine, and normal daily fatigue that occurs later in the day. Finally, we used the gold-standard biomarker of daily hydration status, Sosm.

This study is also subject to limitations. First, given that the study participants were predominantly White, results cannot be generalized to other groups. Future research should confirm findings with Black, Hispanic, and indigenous participants, which prior work has found to be more likely to be dehydrated (Brooks et al., 2017). Future work should also examine this question in nonindustrialized, small-scale populations using culturally-appropriate measures of cognitive performance to assess how hydration and thirst (Rosinger et al., 2022) in more water-insecure settings influence cognition. Future work should also control for indoor and outdoor heat exposures which can affect both hydration status and cognitive performance (Hampo et al., 2024). Further, while the cognitive tasks used in the study were chosen given their associations with executive functioning and emotion regulation (Bridgett et al., 2013) and capture several key components of cognitive ability including inhibition, working memory, and sustained attention, the tasks do not represent the full spectrum of cognitive abilities utilized in everyday life. As a result, it will be important for future studies to replicate and extend the current findings via adding tasks that represent additional cognitive factors such as long-term memory, spatial ability, and processing speed. While we designed the study to have three timepoints, this limited the overall sample size. Power was calculated based on prior work of a moderate to large correlation between the primary study outcomes and this was confirmed (Davis et al., 2020), where Pearson correlation values ranged from .42–.46. However, this study may have been underpowered for secondary outcomes in testing the relationship between hydration status and cognitive performance indicators.

Further, this study did not collect information on how much water and other beverages participants consumed in the prior 24 h and thus cannot assess how individual water intake relates to hydration levels and cognitive performance. However, prior work including cross-sectional and one longitudinal study of hydration and cognition found that it was the physiological (Sosm) hydration status, not water intake, that was associated with cognitive performance and decline over time (Bethancourt et al., 2020; Nishi et al., 2023). Thus, it is more important to measure participants' hydration status via biomarkers than through dietary recall. Further, while subjects were told to avoid high fat foods and caffeine on the morning of the visit, the timing and composition of meals in the prior day were not standardized within and between subjects. Prior work has shown that consumption of a large high protein, carb, and fat meal (1100 kcal) following a fasting state can result in increases in plasma osmolality over the following 4 hours (Gill et al., 1985). However, Sosm is more buffered against acute changes in water intake and diet than urinary biomarkers of hydration (Wutich et al., 2020). While we measured hydration status with the gold standard of Sosm, urine samples were not collected. Future work could also examine urinary biomarkers of hydration in concert with Sosm to examine the relationship. No participants were classified as overhydrated with Sosm <275 mOsm/kg. Therefore, we could not test whether overhydration may also negatively affect cognitive performance as prior work has shown (Bethancourt et al., 2020). Future research should examine the implications of overhydration status on sustained attention and other indicators of cognitive performance in longitudinal studies. Finally, this study is subject to omitted variable bias in which some variables not included in the analysis may affect the relationships between hydration and cognition, such as physical activity levels or sleep duration which have previously been shown to be associated with cognitive performance and hydration (Bethancourt et al., 2020; Rosinger et al., 2019). However, given the within participant design, individuals served as their own controls and so these unmeasured differences should be controlled for within participants, but not across participants.

5 CONCLUSION

This short-term longitudinal study found that dehydration, as measured with Sosm, was only associated with poorer performance on a cognitive performance task that required sustained attention and was not associated with other cognitive performance tasks. Maintaining adequate daily hydration and meeting water needs may be increasingly important for middle-to-older aged adults to ensure proper cognitive function, particularly as water needs increase in future climatic scenarios.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Ann Atherton Hertzler Early Career Professorship funds and Penn State's Population Research Institute is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD041025). The funders had no role in the research or interpretation of results.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES